A-tents at risk

Management of small-scale landform features, Cooleman Plains, Kosciuszko National Park

Optimal Karst Management, PO Box 5099, UTAS Sandy Bay, Tasmania, 70051 Canberra Speleological Society Inc.2

Email: aspate1@bigpond.com

Abstract

Small-scale karst landform features known as A-tents occur in a portion of Cooleman Plains in northern Kosciuszko National Park in New South Wales. They vary in scale from a few tens of centimetres to about two metres. These micro-landforms are rare in limestones and fine-grained rocks generally but occur more widely in granite-type rocks – there they can be many metres in size. These micro-structures are much at risk from natural weathering, inadvertent human feet and, more importantly, at Cooleman, from trampling by feral horses and perhaps deer.

Introduction

A-tents (pop-ups in the American literature) are formed where rocks have had overlying layers removed by erosion relatively quickly (in geological terms). Once the overlying material has been removed, the compressed rock sometimes expands rapidly, forming thin layers. In an example local to Cooleman, more than six kilometres of overlying rocks have been eroded from the granites of the nearby Bogong Peaks in less than 350 million years. Goudie (2004, p 349) under the heading ‘Exfoliation’, states it is:

“The shedding of material in scales or layers, it is often used interchangeably with sheeting or onion-skin weathering. Exfoliation of rock has been attributed to various causes including unloading, insolation and hydration.”

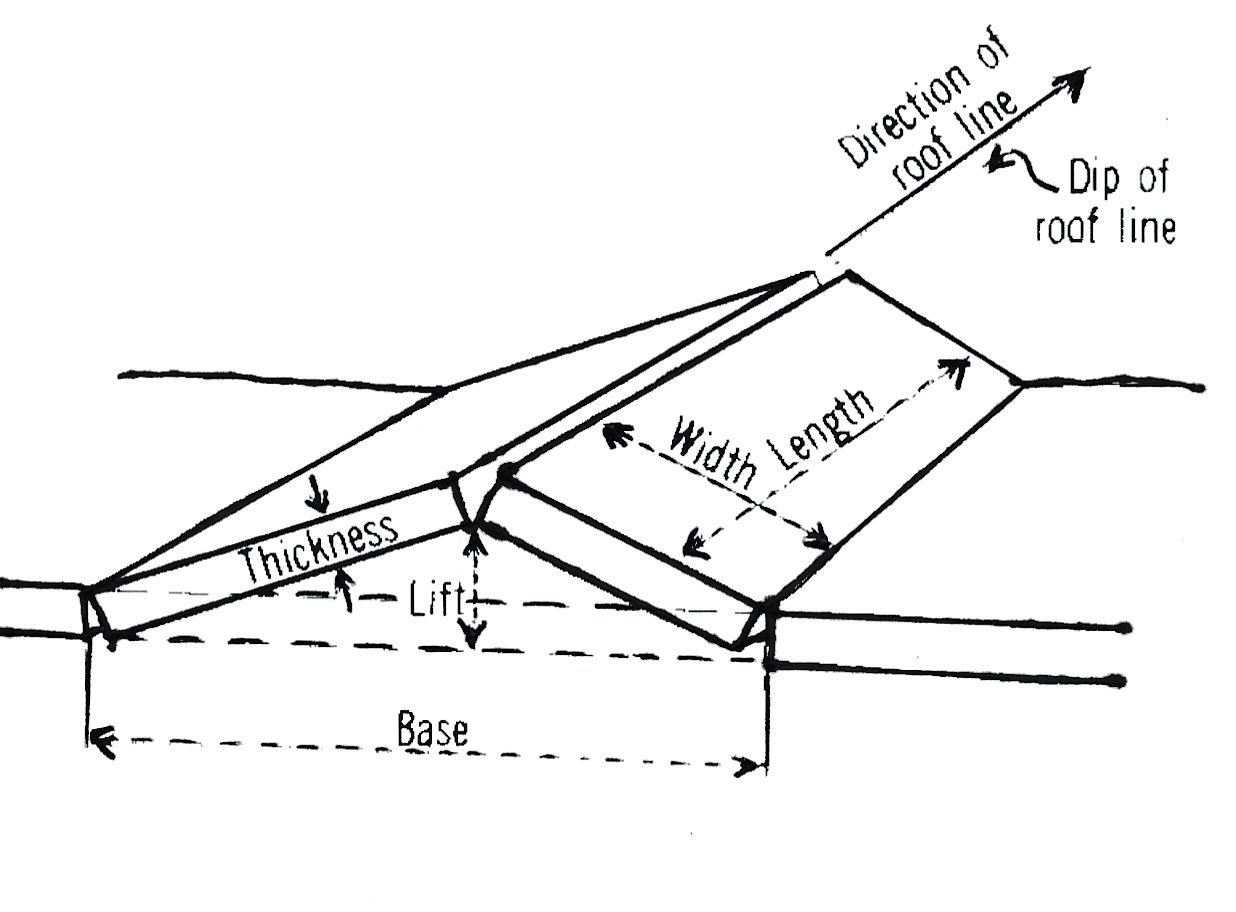

Compression stresses can be released by a process termed unloading or pressure release. Occasionally this produces a small bridge – usually jointed at each end and in the central arch area – termed an “A-tent” (Figure 1). These are widely, if not commonly, known from around the world on a variety of coarse-grained rock types, such as granite.

Figure 1 A perfect Cooleman Plains A-tent. Photo: John Brush.

What are A-tents?

“A-tents consist of pairs of roughly rectangular slabs roofing a shallow cavity in the manner of a wall-less A-tent. The slabs are tightly confined by the remainder of the sheet from which they have been isolated by jointing at right angles to a sheeting joint parallel to the rock surface” (Jennings 1978, p 34).

Harland (1957, not seen but cited in Jennings 1978, p 35) states:

“Rock at depth is under general compression and expands on the removal of overload. While this might take place freely in a direction normal [right angles] to the topographic surface, the rock is constrained in directions parallel to the surface. This results in relative compression parallel to the topographic surface, with consequent fracturing. Extension fracture … allows rock to expand in the direction of minimum stress by fractures normal [right angles] to it.”

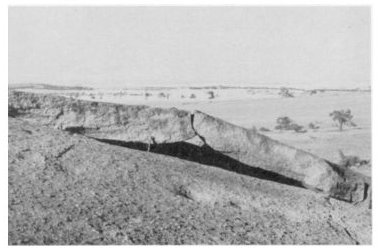

Carbonate rocks are exposed at the surface at Cooleman, Chillagoe and Wombeyan with the overlying material having been removed through erosion by mechanisms such as fluvial processes or the retreat of ice sheets. Solution takes place once the limestones are exposed allowing unloading to happen. Parts of the limestones at these sites have been metamorphosed and developed a coarse grained texture. The A-tents range in size from a few tens of centimetres to greater than two metres in span (Figure 2). Unfortunately, Jennings does not provide detailed dimensions of the Cooleman A-tents other than to state that he measured eight with a lift of up to 14%. Lift is calculated by adding together the widths of each slab and dividing that figure by the base length and expressing the result as a percentage (Figure 3). We have counted more than 30 A-tents at Cooleman – there are very many more. Jennings could only find one at Wombeyan in spite of extensive searching. He reports several at Chillagoe; Lana Little (pers. comm.) knows of three on the Donna Bluff. There are probably many more.

Figure 2 A-tent from Cooleman Plains. Note the lack of a joint at the right-hand end. Photo: Regina Roach.

Figure 3 Schematic A-tent. Redrawn by Kirsty Dixon from Jennings and Twidale (1971).

Related to A-tents are what Jennings (1978) refers to as ‘buckles’; we prefer the term ‘blister’ (Figure 4) these are ovoid to circular features up to around a meter in length. Most are smaller. We have not observed intact blisters but have only seen the collapsed remnants. As with the A-tents, there are dozens of collapsed blisters at Cooleman. Jennings reports them at both Cooleman Plains and Wombeyan.

Figure 4 A collapsed Cooleman Plains blister. Photo: John Brush.

Both the Cooleman A-tents and blisters appear to have formed over a period of time and not as a single event. Many have clean fracture surfaces with no algae or lichen growths to darken the whiteness of the slightly metamorphosed limestone. However, unloading can take place over a reasonable area as a single event as can be seen in this video clip: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wJUHq6nX1iE A variety of sheet-like structures can be seen in the video from Twain Harte Lake, California, on a granite dome.

Distribution

Where A-tents are found on carbonate rocks outside Australia it seems that the unloading and subsequent exfoliation has been due to the retreat of ice-sheets as in north-eastern USA and glaciers in Canada (Jennings, 1978). As mentioned above, we know of them at Cooleman, Wombeyan and Chillagoe. None of these sites have been glaciated for hundreds of millions of years and we must look to solution as the mechanism for unloading in karst regions once the overburden rock has been removed by a variety of weathering and erosion processes. Jennings (1978, p 37) states:

“… the carbonate from which A-tents and buckling have been described above have all been affected by surrounding or neighbouring intrusion; lateral compression has played a part in their compression. At Cooleman … it is likely therefore that residual compressive stresses have been subject to release as a result of solutional removal of rock at the surface.”

We have not specifically looked for A-tents or blisters in other karst areas but, given our familiarity with these features it seems likely that they are relatively uncommon. Given the abundance, variety in size and form of these features at Cooleman, we believe that this site is of national significance for A-tent and blister development on carbonate rocks. Here they are restricted to a small area of no more than a square kilometre on the south part of the plains.

What triggers an A-tent or a blister?

This is a fascinating question. Jennings and Twidale (1971) postulate that the A-tents and related features on the granite inselbergs (domes) of the Eyre Peninsula are formed by earthquakes. Elsewhere the unloading may be brought about by insolation – the heating of the rock surface by sunshine. Sudden cooling brought about by intense rain may well exacerbate the process. Weathering of minerals (hydration) near the rock surface may also produce expansion and thus exfoliation.

Wuddina Rock – A-tents in granite

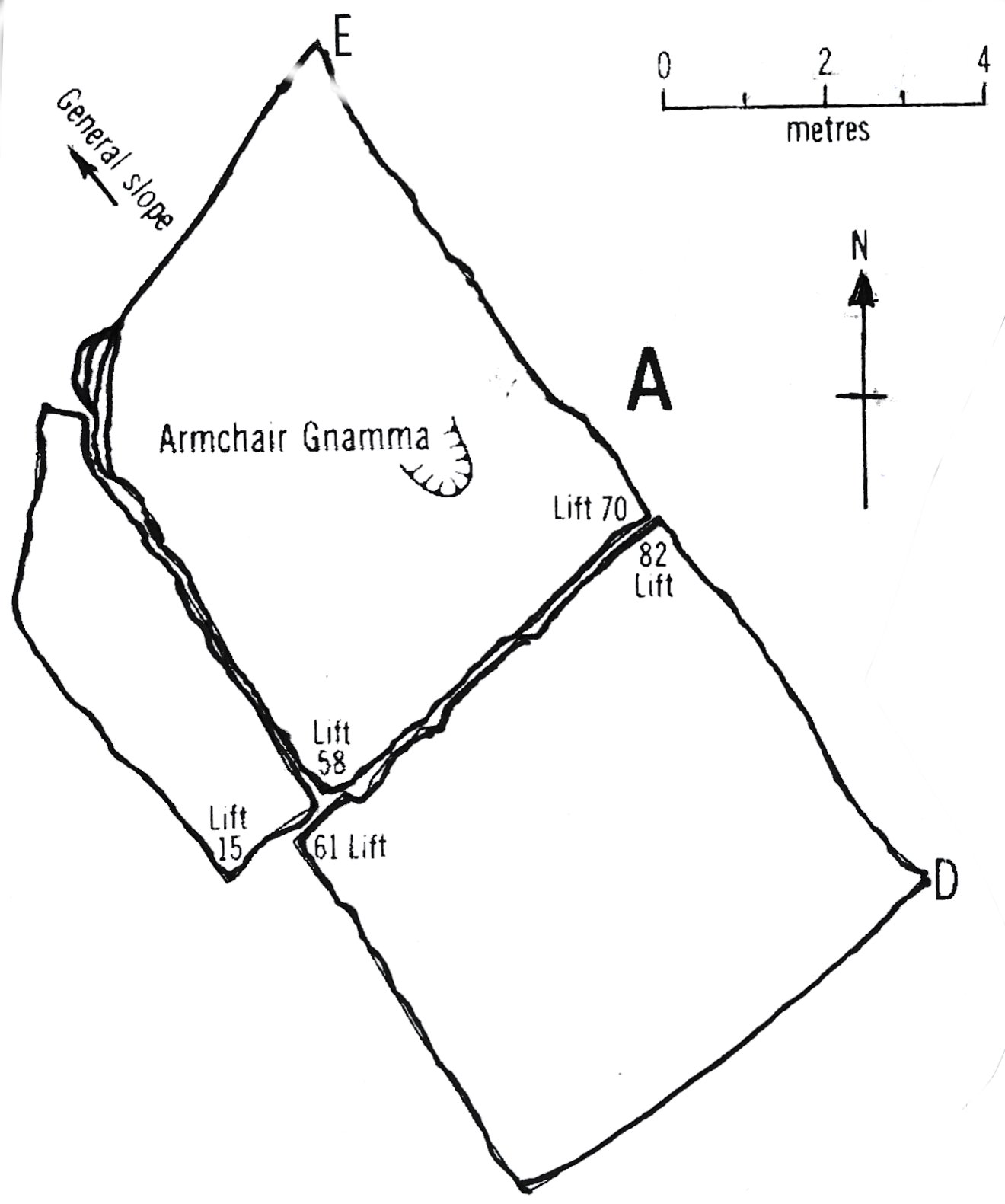

Leaving carbonate rocks aside, cave people from the eastern states pass through the town of Wudinna on the western side of the Eyre Peninsula on their way to the Nullarbor. Wudinna Rock makes a good camp spot on the way west. It lies about ten kilometres north-west of the town and is signposted. Jennings and Twidale (1971) discuss three A-tents there. These are much larger than at Cooleman, for example, as can be seen by the figures below. Jennings and Twidale’s A-tent “A” has lifts of about 58 cm in the front and about 82 cm at the back with an extension of about 10 cm (0.07%). The thickness of the slabs is up to about 60 cm. The weight of the left-hand slab is of the order of 20 tonne whilst the right is about 50 tonne.

Figure 5 Wudinna Rock A-tent. From Jennings and Twidale (1971) as identified as “A”. Note that the photo is taken from the right hand side of Figure 6.

Figure 6 Plan of “A”. Redrawn by Kirsty Dixon from Jennings and Twidale (1971).

Figure 7 The same A-tent in 2009 as Figure 5. Photo: Kirsty Dixon.

Figure 8 The same A-tent as Figure 5 but from the opposite side. Note the flexing of the slabs showing how ‘solid’ rock can flex. Photo: Kirsty Dixon

The problem at Kosciuszko

Horse numbers are increasingly causing environmental problems in Kosciuszko National Park with no readily available management solutions because of the seeming ‘sanctity of the Man from Snowy River brumbies’ and animal rights campaigners. The recent NSW legislation giving feral horses ‘heritage status’ guarantees that the problem will not go away in the foreseeable future – it will exacerbate the tragedy. The A-tents are at risk as are many other aspects of the karst of Cooleman such as the spring-fed bogs. New and eroding horse pathways from feral horses, as well as commercial and recreational riders with iron hoof nails are causing scratching on outcrops and introducing oats and similar weeds to the karst area. The commonly accepted estimate of horse numbers for management purposes is around 6,000 to 7,000 feral horses in the park, but other estimates range as high as 10,000.

Figure 9 Horse-damaged A-tent. Source: Kosciuszko National Park Geodiversity Action Plan 2012-2017, Office of Environment and Heritage, NSW, unpublished.

Figure 10 Note the lengths that NPWS staff will go to on a rainy day to get A-tent images. Photo: Steve Cathcart.

More than 120 years ago, Richard Helms (1893) produced a report on the status of grazing leases at Kosciuszko and expressed concerns about burning and grazing. Again in 1897 (Helms, 1897) he referred to “selfish grazing and burning practices”. The Park was in part created in 1944 because of concerns about grazing raised by Sam Clayton, the Director of the Soil Conservation Service, and others. During construction of the Snowy Mountains Hydroelectric Scheme concerns about loss of dam capacity through siltation arising from erosion caused by grazing by hard-hooved animals led to both the removal of grazing from the high country and very extensive and expensive soil conservation works. The explosion of horse numbers is undoing these progressive steps.

A reactionary and anti-conservation bill introduced by Deputy Premier John Barilaro to ‘elevate’ wild, feral horses to ‘heritage’ status has been assented to by the NSW Parliament. Why not rabbits, hares, foxes, cats, rats, mice, deer, pigs and so on? They have all contributed to our culture in both positive and negative ways.

The resultant Kosciuszko Wild Horse Heritage Act 2018 is in force. The NSW Labor party says it will repeal the Act if elected next time round (this seems likely?). This will lead to much unpleasant debate. But it must be repealed!

The Act calls for a management plan for wild (feral) horses in Kosciuszko National Park. We already have a management plan produced after extensive public consultation. Media comments suggest that any new plan will ‘smile’ on protecting the alpine areas. But the lower-lying treeless frost hollow grasslands such as Cooleman, Cooinbil, Indi and Cowombat Flat and to a lesser extent, Yarrangobilly, are being impacted by these introduced pests. Indeed at Cowombat some years ago we had a cave completely blocked by a feral horse fall into the entrance shaft. Only Ravine and Cave (Clive) Creek karst areas are not impacted as a result of their steep topographies.

Feral horse impacts on Kosciuszko’s karst include multiple (aesthetically unpleasant and sometimes eroding) trackways, destruction of bogs, breaking down of stream banks, siltation of reservoirs and introduction of weeds. In addition to these impacts we have the destruction of the micro-karst features such as the A-tents. There is also the scarring of limestone outcrops by horse-shoe nails.

Figure 11 Horse track crossing limestone outcrop. Note horseshoe nail scarring. Photo: Steve Cathcart.

Figure 12 What are these enigmatic markings on the outcrop? Horse-hoof scrapings? Note the small blister at the top left.

Are there solutions?

We, in discussion with Steve Cathcart and Rob Gibbs from the NPWS, see three possible pathways for protection on the A-tents and related features at Cooleman.

Firstly, removal of the feral horses. The best solution by far! Difficult and expensive – especially given the new Kosciuszko Wild Horse Heritage Act 2018. Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory are experiencing feral horse problems and are moving to control these pests – the constant pressure from Kosciuszko will render their efforts difficult or fruitless.

The second approach might be to fence the entire A-tent area. This would be expensive and, given the lack of soil for inserting posts, very difficult. The rolling terrain with short steep slopes might also make fencing difficult. NPWS has several fenced exclosures across the northern Park to look at the impacts of feral horses on the vegetation. Even if only a few tens of metres a side, the horses consistently push the exclosure fencing over – the maintenance effort is already stretching the NPWS resources. Not a viable approach. Electric fences suffer from the same deficiencies plus the risk of theft.

Thirdly, we discussed the protection of individual A-tents or blisters using metre-scale cages. This would obviously be cheaper – but which features should be protected? But, another ‘but’. Might such cages – although in a little-used part of Cooleman Plain – lead to identification of sites that NPWS deems important – and thus to vandalism. And the materials of any cage would need to be carefully considered to avoid bleaching of the bedrock.

Given the political situation and the lack of resources available to the NPWS, it seems that the Cooleman A-tents will be exposed to horse damage in the foreseeable future. Hopefully, some will escape the heavy-footed pests.

Acknowledgements

Steve Cathcart and Rob Gibbs (Area Manager Murrumbidgee and Ranger, NSW NPWS, respectively) facilitated an inspection of the A-tents and blisters at Cooleman and provided much valuable discussion on the horse problem – and the difficulties facing feral horse management. Graeme Worboys provided the quotation from Richard Helms. Kirsty Dixon assisted with editing and redrawing of Jennings and Twidale (1971) diagrams and provided photos of Wudinna Rock.

References

Goudie, A.S. (ed) (2004). Encyclopedia of Geomorphology, 2 volumes, Routledge, London, 1156 pp.

Harland, W.B. (1957). Exfoliation joints and ice action. Journal of Glaciology, 2:8-10.

Helms, R. (1893). Report on the Grazing Leases of the Mount Kosciuszko Plateau. Agricultural Gazette, NSW, 4:530-531.

Helms, R. (1897). ‘Address to the Royal Geographic Society’, cited in Stanley H. (ed) A History of the Establishment Of Kosciusko National Park, NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service, Sydney, p3.

Jennings, J.N. (1978). Genetic variety in A-tents and related features Australian Geographer, 14:34-38+62.

Jennings, J.N. and Twidale, C.R. (1971). Origins and implications of the A-tent, a minor granite landform., Australian Geographical Studies, 9(1):41-53.